Most of us struggle with our identities.

Our parents may be of different faiths, nationalities, races, or political beliefs. We may have a public self and a private self whose basic values and needs are at odds with one another. The beauty of this problem is that our inner conflicts give us valuable insights into the lives and identities of others.

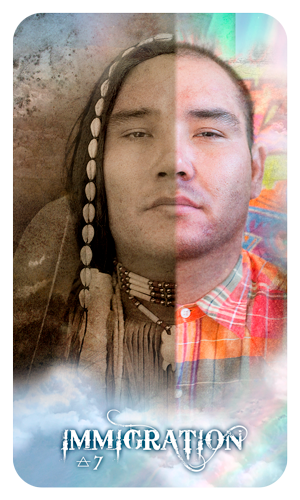

As I was channeling the Transformation Oracle, I came across MJ, a young man who was half Cheyenne, half Caucasian. He grew up on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation in southeastern Montana, yet now works at McDonalds on the Front Range of Colorado. His blood is mixed, as is his cultural experience.

To which family, which Nation, does he belong?

Perhaps he simply belongs to this world—as we all do. Once we unhook ourselves from our tribal or cultural groups, we open to the common ground shared by all humans.

our complex identities help us tolerate others

The United States was formed by immigration. We forced the Native people to adapt to our way of being, making them cultural immigrants on what was their own land. Today’s world migrant situation compels us to wrangle with different religions, languages, and customs.

Will we respond with tolerance and understanding? Or hatred and rejection?

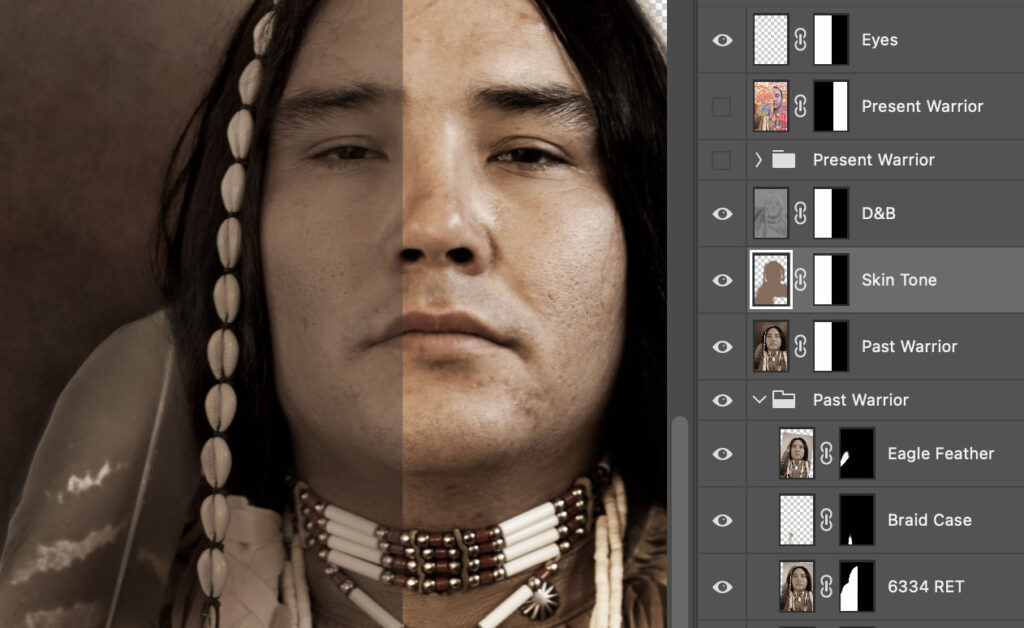

the photo shoot | summer 2014

The principal photography for “Walking Coyote” involved two characters:

• the MJ of today, who grew up on a reservation and later worked at a fast food restaurant

• MJ’s ancestor spirit Walking Coyote, who lived by the old ways

For the contemporary character, MJ wore a bright plaid button-down shirt. The background was graffiti from Brooklyn—a city built upon immigration and home to Pratt Institute where I taught in the late 1980s.

The main challenge was to get MJ, who had never posed before, to call upon his ancestor Walking Coyote, with whom he shared the same name.

MJ went deep inside to conjure his great great Grandfather, a mighty warrior, who had survived by hunting, without any of today’s comforts and conveniences. For Walking Coyote, MJ wore a long black wig with doeskin wraps and a Native necklace, vest, and shells. MJ had earned his eagle feather from Northern Cheyenne Elders. He was adamant not to let me—a woman—touch the sacred feather, so my husband Tim tweaked it into position.

influences & inspirations

The photographer Edward S. Curtis spent much of his life capturing images of Native people in their tribal finery, often staring fiercely at the camera. His images are a remarkable catalog of the personalities, clothing, and ways of life now vanished. The proud or fierce facial expressions show the spirit of people who survived on this land before Western ways irrevocably altered it.

Details of animal bones, fur, feathers, and shell, along with quillwork, beadwork, weaving, and braids spoke of the sacred symbols and stories of the Native tribes. I was intrigued by the canvas background in many of Curtis’s photographs.

Though he took many photographs of indigenous people in landscapes, Native villages, or doing daily activities, Curtis often used a huge cloth as a backdrop. With this neutral background, natural light gave the photographs a distinctive look, often with strong contrast of light and dark on his subjects’ faces. The cloth homogenized and simplified these images, putting the focus on details of posture, clothing and hand-held objects rather than on location.

thoughts as i created …

What happens to your core self when you move your entire life to a different country and culture?

I arrived in the “Wild West” of Colorado after many years in New York City. Before that, I immigrated to the United States from Canada.

My father immigrated to Canada from Germany. I grew up with two languages spoken at home, with a connection to the Old World through my grandmother and others who remained in Germany. We celebrated a German Christmas on Christmas Eve and a North American one on Christmas Day with my maternal grandmother in Toronto.

I’ve done rural and urban, been a country girl and a big city woman. Both identities fit: they are like different clothes worn for different occasions. Underneath, there is only one person.

Some of us know our ancestry back many generations. Others of us are orphans, or only knew one parent. We all need to belong somewhere.

As families change and people move far from their original homes, our sense of identity also transforms. All families and cultures have something of value. What we take from our experience—and what we leave behind—defines us more than conventional measures of nationality, race, religion.

How do you learn to walk in another person’s shoes? Acceptance of others starts with acceptance of our whole selves. When we reach beyond old, limiting identities, we find new family and identity of choice, based on inner values and made strong by compassion and understanding.

Walking Coyote by Sonya Shannon is available as a canvas mantra and matted print.